IBA’27 board of trustees article

Hans Drexler: The Productive City – a future inspired by the past

An International Building Exhibition (IBA) negotiates the future of building, the future of the city and, as a consequence, the future for people living in the city. At the same time, because thinking about the future also opens up structures and processes that determine the status quo, it is equally concerned with the present and the past. Internationale Bauausstellung 2027 StadtRegion Stuttgart (International Building Exhibition, IBA’27), which will have its presentation year on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the Weissenhof Estate, has made a consideration of Modernism one of the five core topics and areas of action. Alongside the urban development of post-war Modernism, the most effective legacy of Modernism is the separation of the functions of cities and buildings. Even today, it forms the basis for planning tools, laws, ordinances, legally binding land-use plans, financing models and ownership structures.

Global megatrends of the era such as urbanisation[i], industrialisation, globalisation and standardisation became enshrined and were encouraged in the modern city. There is no better place to observe the planning and production methods and the mechanisms of the modern economic system than the Weissenhof Estate, which was created in just four months with the help of a field factory. Modernism is how industrialisation was translated into spaces, forms, materials, design and processes. Cities were imagined in the same way as factories, with a focus on optimising traffic flows and efficient processes. The idea was an architecture that could be produced en masse, efficiently and at low cost – like cars. The people living in the cities were viewed akin to factory workers following their optimised patterns of living and working. However, to take the view that CIAM-Moderne[ii] was simply a reaction to global restructuring would be one-sided. It also was and continues to be a driver of development.

The division of labour in society and the separation of functions, initially conceived of only within cities, have led to a distribution of production processes all over the world as part of globalisation (outsourcing and offshoring) in what Steffen calls the »Great Acceleration«[iii]. Fewer and fewer people consider manufacturing, an important cultural and intellectual component in the overall system of economy and society[iv], to be an attractive working environment.

Separation of functions promotes societal fragmentation

The fragmentation and individualisation of society is facilitated by the lack of communal and public spaces. Thomas Sieverts emphasises that the real-life social experience of seeing, meeting and speaking to different people every day are the basic prerequisites for developing a basic understanding of democracy and solidarity[v]. The separation of functions has transformed the public urban space into a space primarily for traffic, with small enclaves left over for public squares and green spaces. There is now a very gradual move toward winning back individual streets and places for people and for public use. Many inner-city areas have been repurposed into shopping centres that offer little other than consumerism. Monofunctional residential areas lack the diversity of urban life. Rigid ideas about modes of living and demand trends result in spatial programmes that generally have a shorter shelf life than the buildings themselves.

We need to develop a new understanding and a new planning practice for an understanding of working and housing that matches the realities of people’s lives in the 21st century and combats social erosion. In Germany’s planning law, the concept of the ›urban area‹ (›Urbanes Gebiet‹)[vi] was added in 2017 to permit commerce, trade, administrative and social uses alongside housing. This marks a return in planning law to a more traditional understanding, where cities were always a place in which housing, manufacturing, services, trade and culture coexisted. The Productive City[vii] of the 21st century is an opportunity to reflect on this constructive, vibrant coexistence and for a new beginning.

The Productive City strengthens a sense of identity and innovation

Ideally, the Productive City is a higher-density city of short distances, making it more environmentally friendly than decentralised urban structures. Per capita land consumption declines as density rises, not just for buildings but also for roads and infrastructure. Utilisation of social infrastructure and cultural facilities increases, allowing for better offerings. When goods and food are produced and traded locally, the city returns to being a dense network of housing, working, social and cultural life.

In recent years, consumers have developed a stronger interest in local, eco-friendly and sustainable products, and they are also willing to accept higher prices for these goods. The reason for this trend is that consumers are identifying with the local products and the cottage industries. Regional products are an important part of a city’s cultural identity. As a result, cities are regaining their original role as drivers of social, political, cultural and economic innovations as well as platforms for exchange and value creation [viii].

The return of manufacturing to cities

For a Productive City, we are looking for concepts that also reintegrate manufacturing and agriculture into the city. Most manufacturing environments are no longer disruptive or dangerous for residential environments, meaning that it is no longer necessary to separate homes from workplaces to the same extent as before. This creates new opportunities for a design mix of working and living in different spaces at different times.

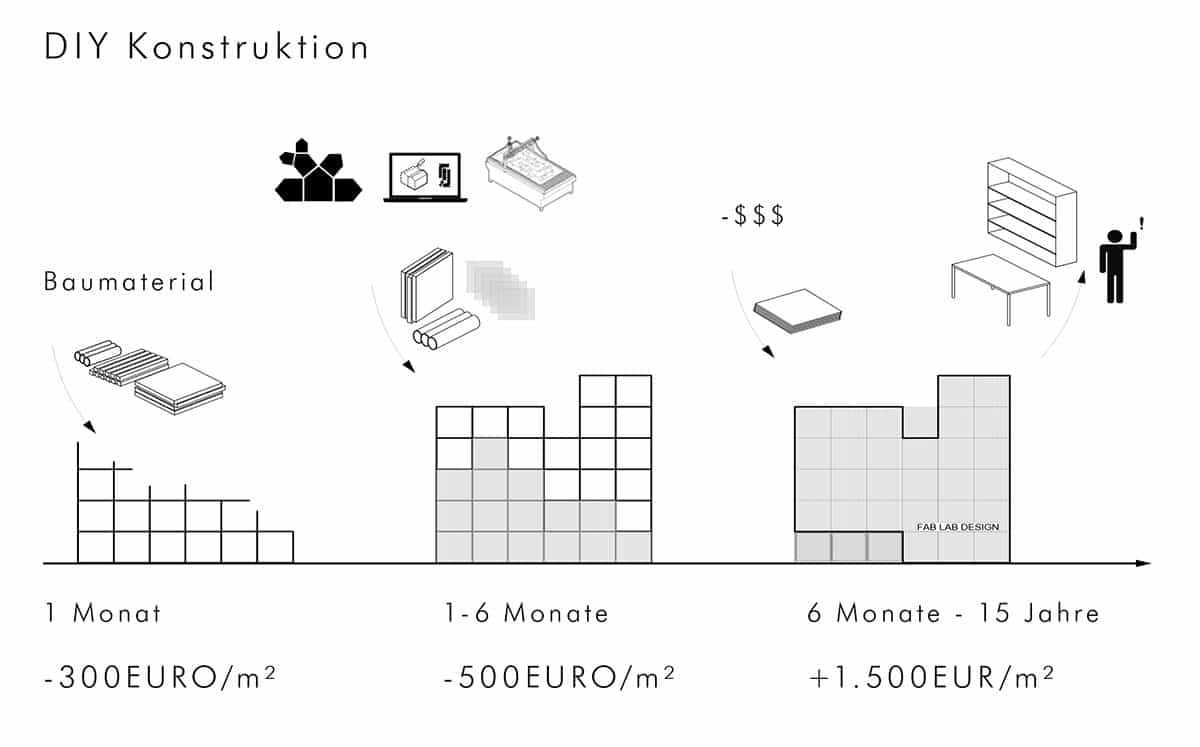

The point of departure for the Productive City is the wealth of possibilities offered by Industry 4.0. The characteristics of this industrial manufacturing are digital connectivity of machines and devices, high flexibility of the manufacturing equipment and lower marginal costs as a result[x] . ›Fab labs‹ (the abbreviated form of ›fabrication labs‹) give an indication of what decentralised and high-level digitally controlled industrial manufacturing might look like in the future. Here, open workshops or labs offer an infrastructure that is suited to small-series production. But establishing this kind of Industry 4.0 is only partly a planning task. We need to develop integrated concepts for economic development, education policy and urban planning in order to create such structures. Fab labs or low-level workshops like these can also play an important role in the integration or reintegration of people into the labour market.

Das Konzept von ›Arrival City 4.0‹ (Entwurf / Credits: DGJ)

The project dgj219 Arrival City 4.0 pursues a participatory and ›self-enabling‹ approach to integration. Under the motto »Home not Shelter«, the refugees can themselves participate in building their own homes. Housing is not only a question of shelter, but a basic right that is closely linked to the question of societal participation. The aim of Arrival City 4.0 is to provide suitable accommodation to people that gives them more than just short-term shelter, namely the long-term prospect of a home.

In developing countries, an influx of refugees often leads to the creation of self-organised, informal settlements with a poor infrastructure and sub-standard building which is then perpetuated over decades to become an urban structure.

Informal settlements cannot be a model for European cities, especially as integration takes place too slowly and too unsuccessfully. In a European context, the self-organised urbanisation of ›Arrival City‹ needs to be translated into a formalised process of self-organisation that meets the technical, urban planning and building culture standards of European cities.

The concept provides a clear structural and design framework for this. For example, in order for integration to be successful, it is essential that the new residential buildings are not recognisable as ›refugee accommodation‹ but are perceived as components of equal worth in the city. By acquiring basic skills to build buildings in the ›fab lab‹, the project can also be considered a self-empowering educational initiative.

The interiors of the houses, such as internal walls and furniture for the dwellings, are created in the ›fab lab‹, which is located in the building. Based on an open source system developed by DGJ, the project is to become part of the ›WikiHouse‹ network, which provides sample designs for buildings and furniture. A simple CNC milling machine is installed on the ground floor, which can also be used by laypeople with a minimum amount of training to produce furniture, internal walls and other building parts. The ›WikiHouse‹ system offers milling and building instructions for manufacturing the basic structure of a CNC milling machine. This means that after the installation of the first ›fab lab house‹, the whole system can be reproduced at very low costs.

›Fab lab housing‹ is a growing and extendable concept that also constitutes a low-investment approach to solve the general housing crisis. Simple homes can be built in a very short space of time with minimal investment. Unlike normal emergency accommodation (tents, containers), ›fab lab housing‹ offers opportunities to be consolidated in the near term into permanent buildings that are a valuable part of the city.

Arrival City 4.0: Konzept (Design: DGJ Architektur)

Manufacturing as an opportunity for city centres

The decline of brick-and-mortar retail creates an opportunity and a necessity to change how we think. Online shopping has led to a fall in sales in brick-and-mortar stores, and this trend has intensified over the past two years during the pandemic. Initially only smaller and medium-sized towns and unfavourable locations were hit, but the decline of retail is now continuing in the side streets of larger cities. It is likely that many shops will not return after the pandemic. This constitutes an opportunity for the Productive City, with buildings where living and working in different ratios and levels of granularity or even use cycles is mixed with individual and shared housing. The proximity to manufacturing also provides a new approach for retail, something already reflected in the many fashion stores with on-site manufacturing in Berlin. Flexible mixed forms like these are more robust in terms of short-term and long-term changes in needs and lifestyles. The flexible buildings can be used and repurposed for the long term, making them more sustainable from an ecological and economic perspective.

Closing materials cycles

Further potential is offered by synergies in terms of energy and materials cycles. For example, the residential buildings could serve as heat sinks for the manufacturing sector. One example of this is the huge data centres in Frankfurt am Main, which together make up the world’s largest internet exchange point DE-CIX. In 2018, the data centres consumed around 1.3 terawatt-hours, roughly 20% of the city’s entire electricity requirements[x] . If the waste heat from the data centres were used, entire neighbouring residential areas could be supplied with heat. On the other hand, all of the buildings could be transformed into small power plants as part of a decentralised energy supply system through the integration of photovoltaic units. It would be feasible to have smart local energy networks that maximise the synergies between the different producers and consumers on the grid.

The next area of action are the local materials cycles. Aligning goods and resources opens up new possibilities for the reuse of packaging (deposit systems) and valuable materials. In this area too, pilot projects could be implemented in the field of construction. Removing and reusing components only makes sense ecologically and economically if the components are not transported too far and are not stored for too long in between. Regional component marketplaces could be created to allow the built city to be used as a raw materials store for building materials and components that are produced constantly when buildings are demolished and converted but are currently not recycled.

Conversion of existing industrial areas to a Productive City

Although the argument has been put forward that a reduced need for retail will free up space in the medium term, these spaces are not sufficient to allow for a transformation to a Productive City. Likewise, new buildings only account for less than one percent of the renewal of existing buildings each year. So if new productive urban neighbourhoods are to be created, this must be approached by mixing of uses as well as deregulation of housing, business and industry in the existing neighbourhoods. This new demand could lead to an even-faster rise in prices and to lower-income households being pushed out.

It would appear to make more sense to redensify and convert the industrial areas near to the centre. These areas have a low development density, generally with just one or two-storey halls and large undeveloped areas, which are used for idle or moving traffic or warehouses but certainly could be built over. The challenge is to protect the interests of industry and business owners equally. This necessity arises from the ownership structure, as the areas can only be transformed if the change does not jeopardise the interests of current and future uses. The industrial area in Fellbach could serve as a test case for such a transformation as part of the IBA’27 Project »Agriculture meets Manufacturing«. For example, the first stage could involve building over car parks, as has already been done for inner-city retail centres.

Spatial organisation and typologies of the Productive City

A distinction can be made between two spatial concepts: If manufacturing units are embedded in the city structure but remain spatially distinct, the term ›enclave‹ can be used. One example is the Wittenstein factory from 2011 in Fellbach, which was built in a central location because it does not disrupt the adjacent residential use in practice. The location and proximity to the residential areas was seen as an advantage of the location. Due to the high security requirements and the production processes, however, manufacturing is spatially separate from the urban space.

Integration goes further when uses are mixed within the same building or within the urban space. The vertical layering of uses offers great promise. For example, within one building the ground floors or lower parts can be used for manufacturing, retail, hospitality and welfare facilities, while the upper floors are used for housing. The coexistence of different uses is also feasible.

A further distinction in use could be made between the inner edges and outer edges of urban blocks. In China, a common feature of urban planning is the ›compound‹[xi], a closed courtyard with residential development, gardens and supporting uses on the inner side and commercial uses on the outer side facing the street as well as residential use and a protected green courtyard inside[xii]. Often the residential buildings are elevated on top of a ground floor that runs through the entire building and can be used for manufacturing or retail. This creates different urban spaces at close quarters, allowing for differentiated use and affording privacy for private and communal spaces.

These examples show that the Productive City is not just a planning task. Spatial and architectural concepts also need to be developed that organise the close coexistence of different uses spatially and temporally which minimise conflicts and make use of synergies. The typology of the ›inside-out blocks‹ in the design by JOTT architecture and urbanism for the IBA’27 Project »Winnenden productive urban neighbourhood« offers an interesting approach, for example, by shifting the more noise-intensive uses into the inner side of vertically mixed building blocks. By contrast, the residential uses on the upper floors face outward to public green spaces between the buildings.

Ways to overcome the separation of uses and of people

An important area of action is (municipal) planning policy. With the definition of the ›urban area‹ in German planning law, politicians have an effective tool that can be used to implement productive urban neighbourhoods despite the fact that the law is still clearly bogged down with the idea of a city separated by functions. At the same time, the Productive City requires the processes to be moderated carefully and flexibly as well as structural and economic policy measures. Blunt deregulation leads to the ousting of certain groups and to knee-jerk reactions to the trends in demand. If new forms of manufacturing and new industries are to emerge in the Productive City, they need a protected space and consistent support.

Spatial and institutional proximity to universities and third-level institutions as centres of research and development appears to offer a promising approach. In Munich, a network of start-ups has grown up around the Technical University (TUM) called ›UnternehmerTUM‹ that targets support at new start-ups. Unfortunately not all universities or third-level institutions are taking advantage of the opportunities offered by these spin-offs and companies. These networks would also be suitable for organising and using the new manufacturing spaces in cities. Another example can be found in Paris, where the municipal authorities have founded an agency called Semaest that leases salesrooms and uses an assistance programme to encourage local companies to set up small businesses and shops[xiii].

Mixing manufacturing, services and housing in a Productive City is bound to lead to friction and to adjustment processes. The mix results in new traffic and in emissions (albeit at a low level); old uses are pushed out and new demand is created. Above all else, the city and the public spaces become a place where people with different lifestyles, needs and daily routines come together. It is precisely these encounters and processes that give rise to the risks but also the opportunities of the city.

Recent decades have brought about an increasing particularisation in how we live and a reduced tolerance of other ideas, people and other ways of living. Single-family homes with their fences and hedges are symbolic of this isolation. Living and working together in the city is the countermodel to this separation of uses and of people. We have to relearn how to deal with friction and with the unexpected. In any case, the Productive City is an experiment. As such, alongside risks and the need to make adjustments, it offers opportunities to adjust our course, and this is something that benefits all of us. IBA’27 provides a framework for us to carry out experiments like these.

Collegium Academicum, Heidelberg (Credits: DGJ)

As part of the International Building Exhibition (IBA) Heidelberg, DGJ Architektur developed, for and with the ›Collegium Academicum‹, an innovative, interactive form of housing to establish self-managed student housing in Heidelberg. In 2014, a group of activists founded the Collegium Academicum to develop a concept for a self-managed and crowd-funded student housing project for 176 students. The initiative provides a solution to rising rents and housing costs as well as anonymous commercial student residences. Collegium Academicum is also a real-life laboratory for housing and building, also with a workshop on the ground floor with a large CNC machine installed. The residents can use the open source system developed by DGJ as a basis for creating their own furniture and partitions.

The self-organised housing is supplemented with the centrally placed common area that gives residents and other urban dwellers space to meet, exchange ideas and start initiatives. This type of project-based learning is particularly enhanced by the building structure, with a ground floor that runs through the building and can be looked into from outside as well as the spatial connection of living, recreational and work zones. Last but not least, the self-managing structure can be seen as an educational process, similar to ›dgj210 Arrival City 4.0‹.

One advance requirement of the Collegium Academicum was to plan a building that can be used as student housing for now but that could be reused or repurposed as housing for the elderly in the future. This is an aspect that is generally not considered in most new buildings today. Consequently, the building was developed with adaptable space in which the inhabitants can themselves reconfigure and negotiate the space requirements for different stages of life. Contrary to the option of generously sized rooms that can be used for different purposes but cannot be changed, the Collegium Academicum developed a small, structured yet flexible construction that allows for the size of the rooms to be changed as needed. This also entails considerable cost savings. The student housing can be offered at a considerably lower cost than is currently the norm for accommodation in Heidelberg.

Notes

[i] It is noted here that the modern vision of a city should be seen as a counter-model to the slums in the cities of the 19th century and was entirely justified in a historical context with regard to the precarious living conditions of the time. The separation of functions resulted from the need to centralise production and from the disruptive effects of factories, in particular noise, emissions and waste water.

[ii] Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (»International Congresses of Modern Architecture« or »CIAM«) was an international architecture organisation founded in 1928 by Siegfried Giedeon and Le Corbusier among others. Meetings were held at regular intervals and served to exchange ideas about architecture and urban planning. CIAM laid the foundations for modern urban planning and modern architecture.

[iii] Will Steffen et al., Global Change and the Earth System, Global Change and the Earth System (Springer-Verlag, 2005), https://doi.org/10.1007/b137870.

[iv] »The argument is that manufacturing cannot and should not be de-linked from typically urban ›knowledge-based‹ activities such as design and R&D. Or, to put it more strongly a manufacturing base is a necessary condition to develop and expand R&D and other high-level services. Production facilities are needed to produce small batches of innovations and new products, and test whether the concepts work in practice and researcher need to stay in touch with the production process.«, Willem van Winden et al., »Manufacturing in the New Urban Economy«, Manufacturing in the New Urban Economy § (2010), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203847732., S. 2f.

[v] Thomas Sieverts, »Städtebau im Zeichen städtischen Nutzungswandels: Perspektiven für den öffentlichen Raum«, Schweizer Ingenieur und Architekt 108, no. Heft 45 (1990): 1285–91, https://doi.org/10.5169/seals-77547.

[vi] § 6a Urbane Gebiete, Baunutzungsverordnung (Verordnung über die bauliche Nutzung der Grundstücke) In der Fassung der Bekanntmachung vom 23.01.1990 (BGBl. I S. 132) zuletzt geändert durch Gesetz vom 04.05.2017 (BGBl. I S. 1057) m.W.v. 13.05.2017

[vii] Definition: The Productive City refers to the physical manufacturing of goods rather than to services. Services, trade and hospitality are integrated in the fabric of the city in a traditional way, and in particular the tertiary sector has gained in significance in recent years.

[viii] Eberhard von Einem, »Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier and Happier«, Raumforschung und Raumordnung 71, no. 2 (April 1, 2013): 173–75, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13147-013-0217-z.

[ix] cf.: Michael Ehret, The Zero Marginal Cost Society: The Internet of Things, the Collaborative Commons, and the Eclipse of Capitalism, The Journal of Sustainable Mobility, vol. 2 (New York: Palgrave Macmillian, 2015), https://doi.org/10.9774/gleaf.2350.2015.de.00007.

[x] Source: Tagesschau: Internet-Knotenpunkt, Frankfurts Rechenzentren boomen, 25.09.2020 04:57 Uhr, https://www.tagesschau.de/wirtschaft/rechenzentren-boom-frankfurt-101.html

[xi] Dieter Hassenpflug and Mark Kammerbauer, The Urban Code of China, The Urban Code of China (Basel, Berlin: Birkhäuser, 2012), https://doi.org/10.1515/9783034612067.

[xii] Dieter Hassenpflug and Mark Kammerbauer, The Urban Code of China, The Urban Code of China (Basel, Berlin: Birkhäuser, 2012), https://doi.org/10.1515/9783034612067. S. 91ff.

[xiii] Wolfgang Kabisch, »Öffentlich-Private Quartierwiederbelebung«, StadtBauwelt Einzelheft | Einzelhefte | Bauverlag Shop 26.2020, no. 228 (December 23, 2020): 51–55, https://www.bauwelt.de/rubriken/betrifft/Oeffentlich-private-Quartierswiederbelebung-Paris-3599662.html.

About the author

Dr. Hans Drexler is a member of the IBA’27 Board of Trustees. He is head of DGJ Architektur in Frankfurt am Main. Drexler has been teaching and researching since 2005 at the Technical University of Darmstadt. Between 2013 and 2018 he has been guest professor for Construction, Energy and Building Technology at Jade University of Applied Sciences in Oldenburg. His research focuses on building construction and prefabrication, timber construction, design methods. More information