IBA’27 board of trustees article

Folke Köbberling: Real-life art projects tell the story of the productive city

Sought-after space

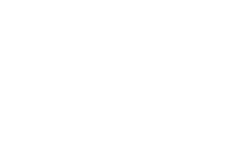

Motorised individual transport is still dominating the public spaces in our inner cities. During the pandemic, the essential nature of the public realm and its open spaces has become very clear. After all, this was the space we were allowed to use during lockdown, where we could meet one another, go for a walk or just spend some time. However, it has also become apparent that the vast majority of public space is used not by people but by motorised individual transport, a development that is constantly intensifying.

»In Berlin, the area taken up by all passenger cars is equal to roughly 17 square kilometres. To put it in context, this corresponds to 214 times the size of Alexanderplatz …” (source)

If we were to use this space differently, for example by de-sealing car parking spaces and using them for urban agriculture, our cities would not only have a different climate but a radically different cityscape.

Cities like Utrecht, Brussels and Pontevedra in Spain, which has been car-free for 19 years, have given motorised individual transport the red card. In Germany, we’re not there yet, and the automotive lobby is still too strong. This is even true for a state like Baden-Württemberg, which has had a Green Party Minister President for many years.

There is scarcely any discussion around the correlation between the shrinking area of land used to produce food on the one hand and the sealing of spaces on the other, leading to an outsourcing of Germany’s land footprint to countries outside of the EU.

Half of the world’s population lives in cities, and this trend is forecast to become more pronounced in the future. 2020 marked Germany’s third summer of drought. We need to change the way we think in order to use cities to provide an alternative to traditional agriculture so that we can cultivate crops in situ. These can then be processed and consumed directly without a need for packaging or long transport chains. This would reduce our land footprint.

Growing potatoes and other vegetables in the centre of town

After the Second World War, Berlin’s inhabitants used the deforested Tiergarten park as a space for growing potatoes and other vegetables.

In an article published in the Berliner Zeitung newspaper on 5 September 2017, Martita Adam-Thkalec wrote: »The British occupying troops permitted this use on a temporary basis. Food was grown on around 2,550 plots of land, and horses and oxen drew ploughs through what was once a park. The Senate designated some spaces as fields to be farmed for fodder.«

Now, 75 years since the war ended, no trace remains of the park’s interim use for urban agriculture. There is just one area at the northern edge of the Tiergarten park that is used by Berlin Waste Management to store leaves in autumn before transporting them to the edge of the city, because composting is not allowed inside the city limits.

During the war years, urban agriculture was vital: Self-sufficiency created subsistence farming, which allowed for independence. This image resulted from an economy of scarcity.

In Detroit, too, people had no other option. There are no fresh vegetables in Detroit unless you grow your own. The big supermarket chains have pulled out of downtown, leaving only gas stations and convenience stores behind. A city that once had two million inhabitants has shrunk, and out of necessity has emerged a culture that serves as a blueprint for lots of communities around the world. The wasteland left over after the city shrank has been used for urban gardening and urban farming projects as neighbourhood projects. It’s not just about growing food, but also about bringing community projects to life. There are no fences and no boundaries, and the spaces are directly adjacent to the city’s neighbourhoods.

According to the Keep Growing Detroit map, 484,250 pounds of fresh produce were produced in 1,941 gardens in Detroit in 2020, with almost 30,000 people getting involved. This is equivalent to a return of 1.5 million US dollars. Detroit has become a self-sufficient city out of necessity, using the spaces that were freed up when the city shrank and that are no longer used to generate a return.

Young people from all over the US come to Detroit to practice agriculture on their newly acquired land using a wide variety of different methods. This means that gardens are used highly efficiently to increase the yield of fresh produce. These urban farmers install »aquaponics« and document the yield off their land in great detail.

Temporary farmland in New York and Los Angeles

In cities like New York and Los Angeles where space and land are at a premium, it is much more difficult for urban farming to get established. But even there, artists’ projects have shown that it is possible.

Back in 1982, artist Agnes Denes created a symbol of urban agriculture in downtown New York with her work »Wheatfield – A Confrontation«.

Built on a landfill in Lower Manhattan, just two blocks from Wall Street and the World Trade Center and facing the Statue of Liberty, her urban garden flourished. According to the artist’s website, the value of the land she used was estimated at 4.5 billion US dollars. The site has since been developed and is called Battery Park Landfill. Nowadays we can scarcely imagine how it was possible to plant an 8,000 sqm wheat field in the midst of the world’s most expensive real estate, yielding more than 1,000 pounds of healthy, golden wheat.

In 2005, Farmlab together with artist Laura Bon created a similar image of productive urban agriculture, this time in Los Angeles. The work »Not a Cornfield« involved planting corn on a 32-acre site set against the backdrop of skyscrapers. »Not a Cornfield« sees itself as a living sculpture created in collaboration with staff and volunteers for one agricultural cycle in 2005 and 2006. The project sprang from the desire to return leached-out wasteland that was once a fertile urban area to its arable state as a symbol of hope and renewal. The intention was also to speed up the process of transforming the site, owned by the State of California, into a State Historic Park.

Another artist’s project, albeit on a different scale, is »Edible estates – Attack on the front lawn« by Fritz Haeg. Los Angeles is made up of millions of single-family homes. Most of those homes have a lawn out front, but they are generally only kept to look good and to separate a property from the next-door neighbour. Through his work, the artist and architect Fritz Haeg has succeeded in transforming these domestic front lawns into highly productive, edible landscapes.

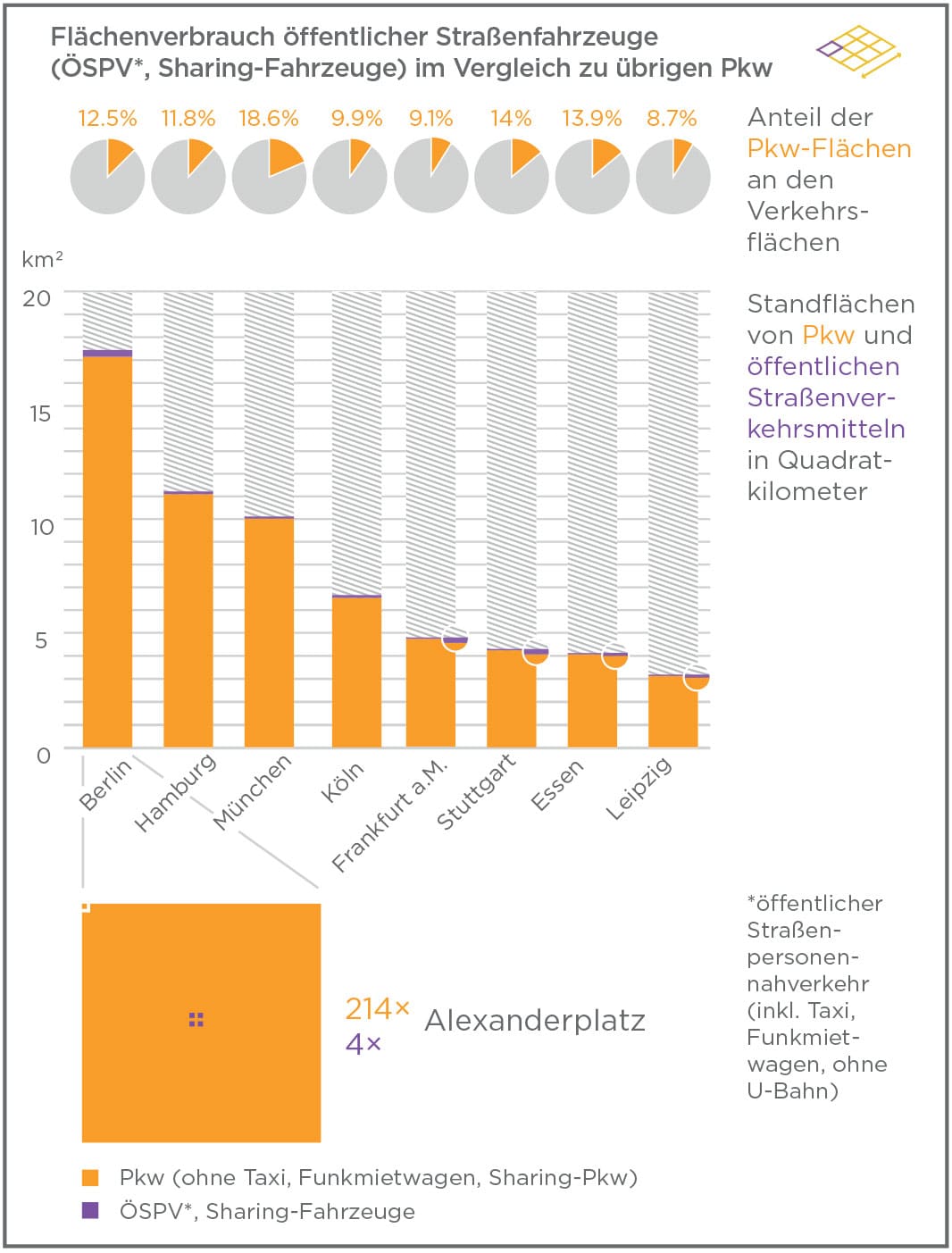

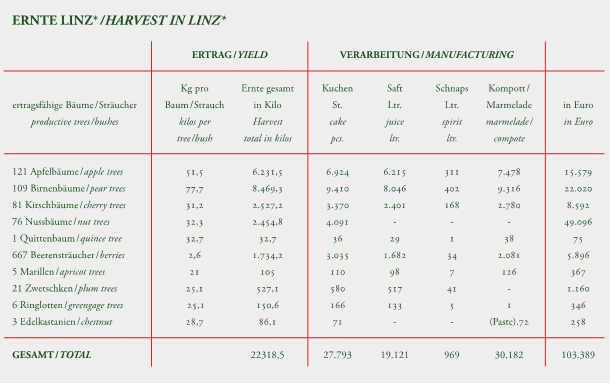

In 2005, Berlin-based artist Ella Ziegler used existing cultivated fruit trees and berry bushes in the city of Linz for her work »Harvest Linz«. She compiled a list of the precise locations of these trees and bushes and created a map of the abandoned trees. The fruit falling from the trees was often regarded as a nuisance. »The fruit trees, a clear indication of a formerly agricultural structure of urban space, are ›managed‹ nature and collective property at the same time«, wrote Ziegler. »I contrast the obsolete use of the trees with the calculation of the profits in cake, juice, schnapps and finally in money. The total value is €103,389.« After the project, the cultivated fruit trees were assigned to sponsors who ensure that the fruit from the trees is put to good use.

In Fellbach, there is the IBA’27 Project »AGRICULTURE meets MANUFACTURING«. Fellbach also has meadow orchards and since last year it even has a marketplace for the orchards. Like Ella Ziegler’s artist project, the municipal authorities in Fellbach want to bring together owners of meadow orchards »who are no longer willing or able to cultivate their patch with people who don’t own a patch of ground but would like to tend one. The aim of the marketplace for the orchards is to provide a forum for linking up ›supply and demand‹« (Source: Stadt Fellbach). It’s an excellent idea in view of the many pear, plum and apple trees that we have in our country and the fact that fruit is rotting by the roadside while we buy imported fruit in our supermarkets.

So let’s go back to the start. How can we move from using sealed spaces to transforming them into productive space? In Germany, the construction of housing, roads and business parks destroys a piece of our natural environment equivalent to the size of a football pitch every fifteen minutes. Roughly 120 million hectares of agriculturally used land outside of Europe is needed each year to satisfy the European appetite for food and consumer goods alone. Very few people are aware of this indirect land use, also described as »virtual« land or »land footprint«. The worrying aspect is that the negative environmental impact is outsourced to the producer countries, where land is leached out or overfertilised, poisonous pesticides harm the environment and untouched woodland is converted into agricultural land.

This is why it is so important to start to de-seal existing sealed spaces.

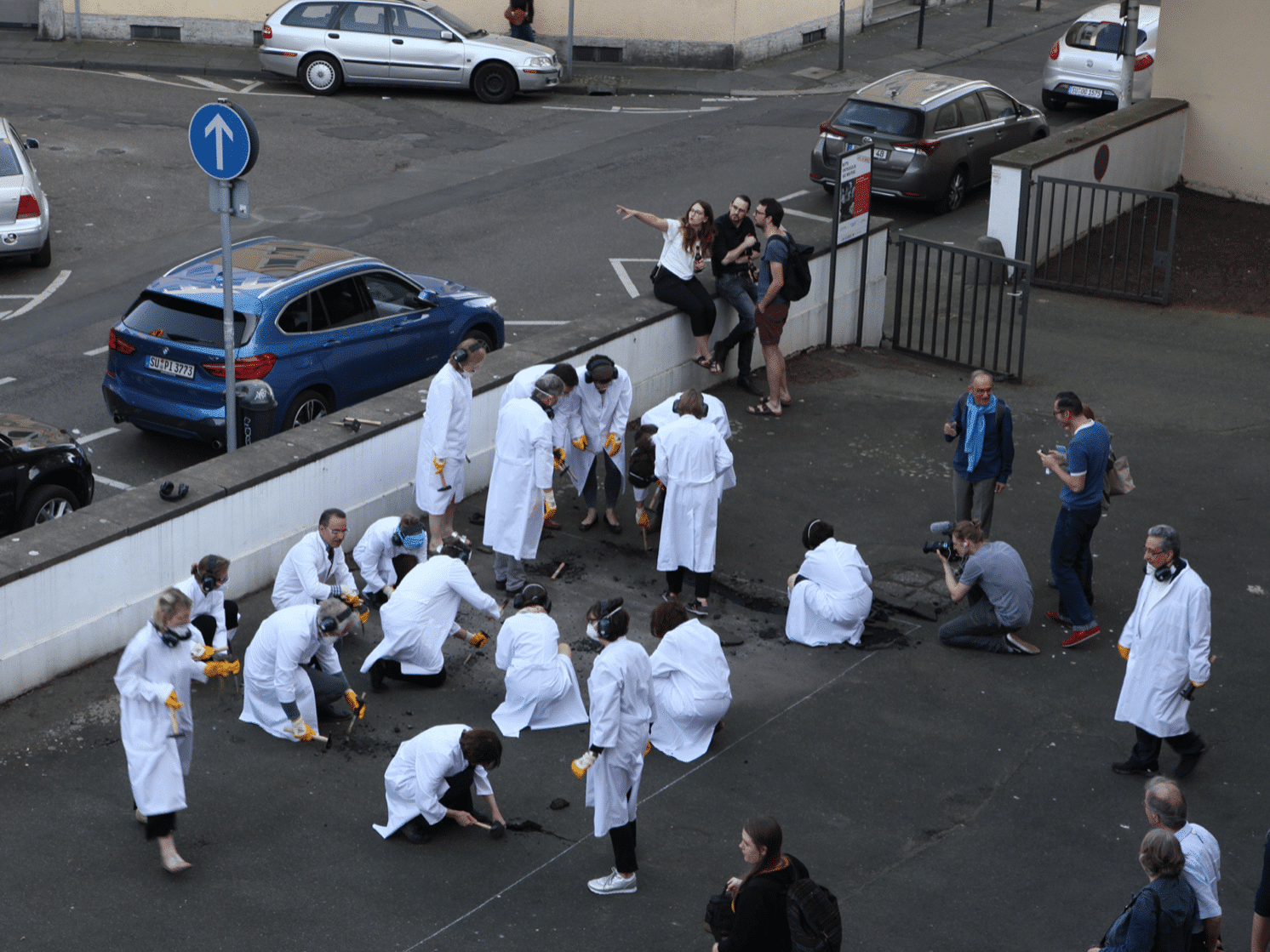

Image: @Reinhard Kiehl

Image: @Reinhard Kiehl

My artistic project »Testphase 2« as part of the exhibition »Zur Nachahmung empfohlen!« (ZNE!) (»Examples to follow«) in a car park in Bonn is dedicated to de-sealing paved surfaces.

»Roughly 45 percent of all surface area used for housing and transport in Germany is currently sealed, meaning that it is developed, covered in concrete, asphalt, cobbles or other types of paving. This results in the loss of important functions of the soil, particularly water permeability and soil fertility. The rise in the percentage of surface area used for housing and transport means that soil surfaces are being sealed at an increasing rate«. That’s according to the website of the German Environment Agency.

I invited the public to break down four square metres of asphalt into tiny parts so that they could appreciate the force exerted by a pneumatic hammer in normal circumstances. They could see de-sealing as a feat of strength and experience the resistance of the material. Equipped with a hammer and chisel, the visitors were given the opportunity to experience initial moves toward winning back sealed areas in a sculptural context. This created a minimal space for possibilities.

If we could succeed in making our towns and cities car-free and de-sealing parking space and we were allowed to make compost inside the city limits, we would also reduce our land footprint.

About the author

Folke Köbberling, born in 1969, lives in Berlin and has been a professor of artistic design at the Institut für Architekturbezogene Kunst (IAK) at the TU Braunschweig since 2016. She has participated in numerous national and international solo and group exhibitions, many of them in collaboration with the artist and architect Martin Kaltwasser. Among them exhibitions at the Martin Gropius Bau in Berlin, ZKM Karlsruhe, Lentos Museum, Ruhrtriennale 2012, Kunstverein Kassel, Museo El Eco in Mexico City and many more. Folke is a member of the IBA’27 Board of Trustees.

More information